Mapping a rural region’s “community food assets” reveals isolated islands of opportunity in a sea of corn and soybeans. LSP’s Scott DeMuth says now is the time to connect the dots and create a new relationship between farmers, eaters, and the places they live in.

“You know, when I talk about rural economic development, from my perspective, you look at things like putting the culture back in agriculture, right? And part of that is foods and food traditions. It’s about local foods and local food traditions that exist. And then it’s also the other big piece of that — I mean, it’s the arts and music piece. It’s the things that attract people to a community and make them want to stay and make them want to put down roots.”

— Scott DeMuth, LSP regional foods organizer

This conversation is taken from a recent LSP Ear to the Ground podcast and has been edited for brevity and clarity. Listen to the full episode of Ear to the Ground 347: Bite-by-Bite on your favorite podcast platform or here:

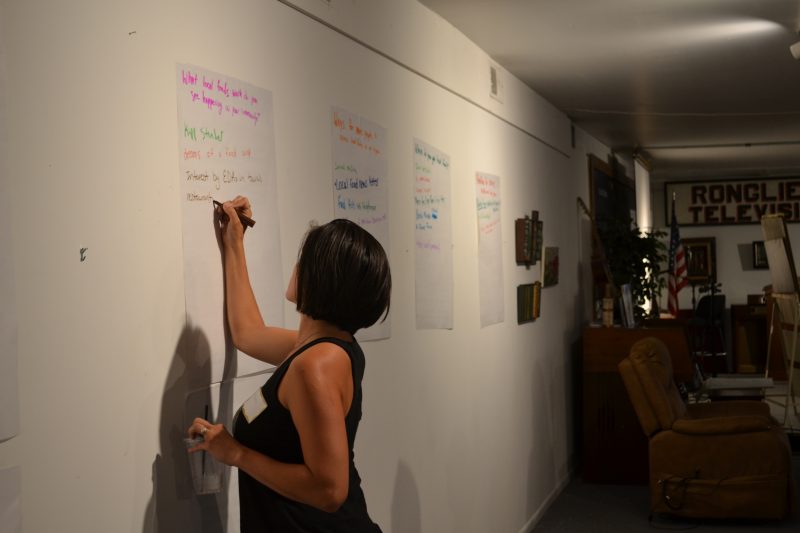

Brian DeVore: During the past few years, I’ve spent a fair amount of time staring at large sheets of paper taped to walls in western Minnesota community centers and other venues. These sheets of paper document what assets local communities possess in order to develop food systems that feed local people while supporting local farms and other business enterprises. The information populating these community food asset maps has been provided by farmers, small business owners, and local government officials, among others.

These people were invited to supply that data by the Land Stewardship Project, which, during the past few years, has been busy launching a Community Food Systems Initiative in the Upper Minnesota River Valley. When taken as a whole, what’s striking about these asset maps is how many so-called community food resources are already present in the region. There are grain and meat processing facilities, commercial kitchens, aggregation warehouses and cold storage spaces, as well as grocery stores, schools and restaurants willing to provide locally produced meat, dairy products, fruit and vegetables to eaters. But all these dots on the map are a little like disparate community food islands floating in a sea of commodified corn and soybeans.

What’s become clear to LSP and our allies in this work is that in order to create what food system analyst Ken Meter calls a “community food web,” connections need to be made between these isolated islands. For example, we need to figure out how to efficiently haul all that meat or produce from all those local farms to the grocery stores, schools, restaurants, and individual eaters who want that food. That’s why LSP has been following up those asset mapping sessions with meetings where farmers can connect with other links in the food chain.

LSP organizers have also been working with allied organizations, local businesses and local governments to brainstorm ways to make the best use of the food assets already present, and to determine what could be done to fill in the missing pieces. One of the people who’s been doing this work is Scott DeMuth, a food systems organizer for LSP who lives in Granite Falls, a town of around 2,700 people that sits on the Minnesota River in the western part of the state.

On a recent summer evening, Scott and I got together to talk about LSP’s food systems work while nighthawks circled overhead and trains hauling commodities boomed through town. Scott talked about what the community asset mapping project revealed, and some of the ripple effects, economic as well as social, that can occur in a community when it focuses on building a food system not based on exporting raw commodities. He also shared how, as a resident of the area, building a thriving food and farm system hits him on a personal level.

Brian DeVore: So Scott, the other day you were talking about some of the local food systems work that LSP is doing, and it’s something that we’ve kind of relaunched in the last couple of years here in western Minnesota, kind of in the Upper Minnesota River Valley. And one of the things that I think is really interested is that one of the ways you kind of started out relaunching some of this work was you did something called community food asset mapping.

I know you worked with Ken Meter, who’s a food systems analyst. He did an analysis of what economic value we would be getting if, for example, we just bought a certain percentage of food locally; it doesn’t take 100% of the food to be local or whatever. It was a pretty outsized impact.

Scott DeMuth: When we started this project, we actually started it shortly after the pandemic and things started reopening. So we kind of started initially with, interviewing members and doing some community listening sessions, and a lot of that was really just to hear from members and folks in the community about what they wanted to see. What Ken Meter really brings to the table is this idea of community food webs, and this idea of not just the economic value, but also just the social values that also go along with local foods. And the analogy I like to kind of point out is that when I first moved rurally from Minneapolis and was getting my oil changed, I was getting it done locally. It was probably, geez, probably 15 bucks more than, if I just, like, went to one of the near towns, Marshall or Wilmer. It’s just like, why don’t I just go there? Why do people pay more for the local service?

For a lot of people, it’s about paying for what they want to see around here. They’re supporting their neighbors, and I think that’s a big part of it, but it’s also something that they want to have. They want the convenience of having it here in town, versus having to drive 30-45 minutes to go get your oil changed, to get other car services. So it’s not just about the oil change, it’s also having someone who can repair your car, having all these other services here in town. And yeah, you pay a little bit more for it, but that’s also someone who’s your neighbor; their kids, you know, are going to the same school as your kids. It’s just fascinating to me that that same idea hasn’t quite translated over to food yet.

After the pandemic, I think that’s when people started to think about that a little bit more. It was just a little bit more immediate. I think it was the first time many Americans experienced things like going to the store and not having particular items available, not just because they weren’t in stock, but because they might not ever be in stock. With some of the shutdowns and supply chain issues, people started just taking it a little more seriously about where their food is coming from. That’s kind of where that stuff started from for us, at least, when it comes to local foods.

I think there’s a lot of pieces that are just part of our LSP values: soil health, having and supporting more farmers on the land. But I think there’s this other big piece of our mission that’s also about building strong rural communities, and local foods are such a big part of that. And Ken Meter did some math and looked at just our population out here. And if every person was spending $5 a week on local foods, I think the impact was somewhere around $50 million alone. That’s a huge economic impact for a region by just making a small lifestyle change.

And we’re also at an interesting time where food prices are rising for everyone. I don’t know if it’s always going to stay this way, but we’re in this kind of interesting moment where local foods, at times, are pretty competitive price-wise, when compared to other products that are out there. I know for local milk right now it’s pretty comparable gallon-to gallon-compared to buying it off the shelves. There’s a lot of things baked into that, it’s an interesting moment to be in.

Brian: So yeah, that’s that whole outsized impact of, like you said, just $5 a week could produce this incredible kind of ripple effect in the economy. So instead of chasing big CAFOs and methane digesters, what we should be chasing is some of these changes in the local food system.

Scott: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think it’s the dollar impact of that. It’s also just the community impact. You look at the amount of money and tax breaks that go into some of these projects and the jobs that you’re creating, you know it’s not that significant when you look at the number of people that are actually being employed, versus when we’re talking about local foods, right?

We’re talking about this idea of even just more farmers on the land. And you know, the impact of that isn’t just purchasing food from local farmers, and there’s a lot that’s baked into that. And the multiplier of that — those dollars that you spend with a local producer circulate in your community so many more times that the economic impact is like for every dollar that’s spent it has the economic impact of another dollar and 60 cents versus you go spend that dollar at, let’s say, a Walmart, maybe 50 cents is being returned back to the community, because the rest is going to suppliers and transportation and shareholders. I mean, you look at Wall Street’s investment, and most of the money is going to shareholders.

Then, when we talk about those producers on the land, oftentimes we have people who are starting families. We have their children, and those children are then going into schools. So then you have more need for teachers in our communities, which is creating more jobs. You have those people then going and buying supplies locally and spending their money locally. So it’s not, I wouldn’t say, a magic bullet, but it’s interesting the way in which investing in local food has this trickle effect that solves a lot of the issues, or addresses a lot of the issues that that rural communities are facing in terms of economic development. You know, the “brain drain,” or the flight of young people from rural communities? It seems to address issues like that, even if it doesn’t solve all of it.

Brian: With the row crop commodity system and large scale livestock system that dominates, there’s a lot of sound and fury there. It’s really impressive to look at the figures and say, this is how large of an economic impact it’s having. But when you look at the community, that wealth is not being retained locally, so it’s going somewhere else. It’s going out of the community in train cars and semi-trucks and all that.

Scott: And you look at even just the amount of inputs that go into those commodities, and where those inputs are coming from, and they’re coming from, oftentimes, large multinational corporations. So those dollars that you’re spending on fertilizer, nitrogen, etc., yes, some of those dollars are being retained in the community, but the rest of it, they’re going elsewhere, and they’re going to these investors and giant companies that aren’t in the local community. And then you’re dumping tons of nitrogen on crop fields and much of it gets flushed down the river.

The thing I like to point out too is that local foods, outside of farm-to-school, isn’t subsidized. You have subsidies going into commodity crop subsidy programs like crop insurance, right? We really are kind of talking apples to oranges when it comes to two really different types of food systems and the way they are supported.

Brian: So tell me a little bit about community food asset mapping. What does that consist of, and what is it that you are looking for, and what have you discovered in this area here?

Scott: So when we started this food systems work out here, a lot of what we had been hearing from folks was that there isn’t a local foods movement there. There used to be a really robust one, and now there isn’t one.

And we kept hearing all these little pieces of things that used to exist, or that might be here. This person might have some equipment, or that person might have a mill. Meanwhile, I’m in this very privileged position to be able to hear from 30-plus people about all the exciting things that they individually are doing around local foods, and I’m hearing about all these different opportunities. And so the asset map itself was like the end product, but what really came out of it was bringing people together in these different communities and in different towns, having them come together and have some of those conversations together.

So what are the cool things that people are doing in terms of local foods? Where are the farms that they’re buying food from? What equipment do they know about? Where are the buildings that are empty and not being utilized in the communities? So we were using the answers to these questions to literally just create a map. We draw a map on the wall, and people are putting Post-its on to kind of identify these assets. Through that, we’re trying to create and facilitate connections between people and trying to get some ideas going.

Brian: It’s like two ships passing in the night. There’s all these great things going on, but they’re not communicating. I remember going to a couple of those meetings where the Post-it notes have been put on the walls. I’m like, wow, yeah, when you look at that, you see the the trees for the forest. It’s pretty impressive.

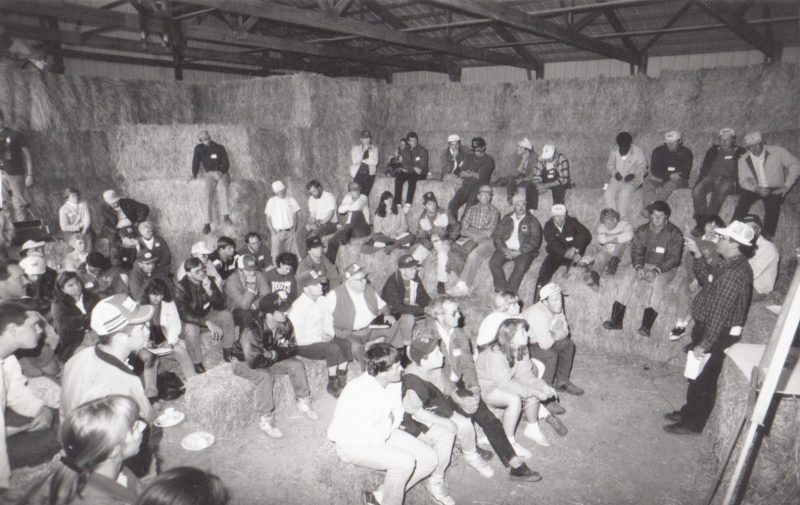

Scott: I mean you see where the opportunity is. For us, the nice thing about it too is we had some folks at the sessions where we got to hear about some history and about things that used to be there. And we also had a couple sessions where we had producers there with people who were looking to buy local food, and they were able to connect. It wasn’t anything grand in terms of infrastructure, but just those kind of connections of building community.

One of the things that we’ve been hearing from folks when they move out here is where do I go to find local foods? At this moment, we don’t have a resource guide. We haven’t had some of the things that used to exist in terms of Pride of the Prairie and the local foods guides. The Minnesota Grown directory would probably be the closest thing that someone could find to identify sources of local foods.

Brian: It’s like, there are all these dots out there, but there aren’t the lines connecting the dots, right? And I guess that’s the role that organizations like LSP and some of these other groups can play is literally just simply bringing people together into the same room. They go, oh, you’re doing that. I actually need this processed, and you have the processing, or you have the transportation kind of thing. Is that something you kind of saw?

Scott: We heard that pretty early on, too, from a lot of folks. We asked what role LSP should play in the food system out here and the answer was: bring people together. We heard that from producers and economic development organizations. And that’s something I think LSP does fairly well — bring people together.

I think that’s the part that’s the most replicable of this is that it doesn’t really take much in terms of experts to host something like this. What you really need, though, are the people and getting the people to the table. And I think we have the members in this region and enough history that we can reach out to people and know that there’s going to be 15-20 people that are going to show up for a meeting.

And then we’ve been actually focusing on institutions in our region. Again, I mentioned farm-to-school. I think that’s one of the things we’ve heard from a lot of producers about where we should be focusing our energy right now is trying to build those relationships with those institutions. Also, there are hospitals and food shelves. So I think those are three institutions that we’ve really been focusing on.

Kind of the thought process for us is by going for some of these bigger wholesale markets we have to create some infrastructure and coordination among producers and in terms of aggregation and distribution to be able to meet the needs of those markets. And by doing that, we’re also creating a lot of the same infrastructure that would also allow producers to sell more retail.

Rather than having to find 100 customers in a community, you have one customer, which is the school district. So that’s kind of been our approach at the moment. To do that, we need to answer questions like is there a commercial kitchen? Is there a way to process the food? Transportation issues and aggregation are other big challenges that people are facing.

When you look at costs, I think distribution is a big one for folks, and having the volume of sale needed to really make those costs or make the transportation costs worth it. And so part of the asset mapping was identifying a lot of things like commercial kitchens in our region, as well as refrigeration space. And you know, we don’t have a lot of open, usable refrigeration space. We do have a lot of commercial kitchens that people could be using.

A lot of this is about repurposing existing space. The Madison Mercantile in Madison, Minnesota, for example, is taking this old mercantile building, which is just a huge square footage of space, and creating multiple incubation spaces in it. They are also looking at converting part of that into cold storage that producers could use, and that could be a potential aggregation and transportation hub.

Brian: You don’t have the luxury here of being close to, say, the Twin Cities or another metropolitan area, where that can be your market, and you can say, well, we’ll just produce for that urban or suburban market. I would figure distance from major markets is a challenge, but also maybe it’s an incentive to become a little bit more self-sufficient in the region?

Scott: Yeah, absolutely. We’re kind of in a really interesting sweet spot in some ways, where there are multiple producers that are selling into the Twin Cities, and it is two-and-a-half hours away, so you can definitely have that as part of your sales strategy.

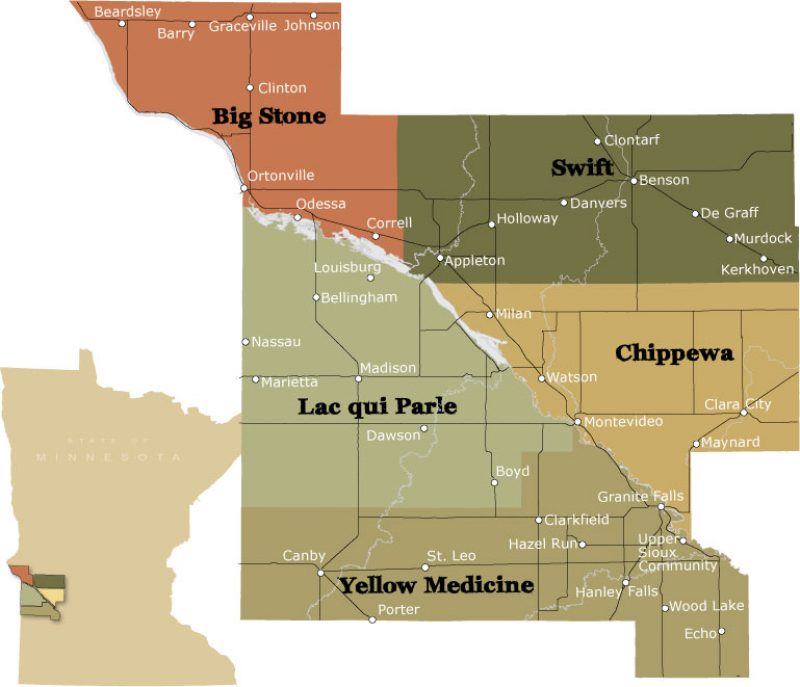

But we’re also far enough away where it’s not the sole focus for producers, and we also have a lot of producers and folks just generally in the area that have a strong commitment to just this region in general. I think that’s the other kind of advantage that we have. Things like the Upper Minnesota Valley Regional Development Commission — it’s kind of a five-county economic development agency, and they’ve invested a ton in this region around just trying to attract people to moving to this area and to putting out roots out here by promoting jobs and recreation. They’ve been one of the folks behind the annual Meander Art Crawl, so they are also investing in culture and arts in the region.

I mean, we’re here right now in Granite Falls, which is another really good example of a community that has invested a ton in local arts, and what you’ve seen as a result of that is a pretty vibrant downtown compared to a lot of other communities of similar size. I mean, this is a population of 2,000 people, and you have a brew pub, you have two different art buildings. We have a local barber shop, and we have a really awesome bakery owned by a local farm family — Carl’s Bakery, which is owned by the Streblow farm family. I don’t know if any one of those would be able to succeed as well as as they do without each other, and it’s great to have this really vibrant arts community built up around this as well.

You know, when I talk about rural economic development, from my perspective, you look at things like putting the culture back in agriculture, right? And part of that is foods and food traditions. It’s about local foods and local food traditions that exist. And then it’s also the other big piece of that — I mean, it’s the arts and music piece. It’s the things that attract people to a community and make them want to stay and make them want to put down roots.

Brian: Going through this process, was there anything that super surprised you? You probably had some assumptions coming in, but was there anything that really surprised you?

Scott: Going through the asset mapping and having the meetings and talking to folks, I think the biggest surprise was that we’re talking about the Upper Minnesota River Valley, and there’s this five-county region, but we have multiple agencies all working out here on local foods, and we haven’t been really coordinating and talking with each other.

For a five-year period, there just was not much coordination. It’s not just the farmers that aren’t coordinated; it’s the organizations and agencies and that type of thing, and it’s a challenge because everyone has their own work plan, has their own projects that they’re trying to move forward. But we have this unique opportunity out in our region, where we have multiple agencies working over a similar, shared geography. So, when I talk about those five counties of the RDC, the Upper Minnesota Valley Regional Development Commission, it’s also the same five counties that operate the Statewide Health Improvement Program (SHIP), which focuses on nutrition and those kinds of things.

And then we have Prairie Five, which is another agency that is doing multiple things. They’re doing transportation out here. They’re doing senior meals, they’re helping with food shelves in those same five counties.

And LSP’s work on local foods has started with those same five counties. So part of our work over the last year or so has been really trying to figure out how do we coordinate our efforts and really work on them together? And so farm-to-school has been a current one that we’re all currently lined up on. And there are some really exciting projects hopefully we’ll be able to talk about in the future as a result of that.

Brian: Speaking of the future, what are the next steps, and are there one or two things that you’re seeing that like, oh, okay, if we could get this mechanism in motion, this would really help us move forward on taking this beyond just the mapping phase?

Scott: Yeah, we’ve been working with the Regional Sustainable Development Partnership, and we’re trying to set up a list of 10 to 20 products that local producers can produce that would be competitive price wise and that could be marketed via farm-to-school. o that’s kind of our next phase is trying to identify some of those products for school districts in our region, and do some relationship building with those food service directors.

We also have done Food Forums where we do producer and buyer matchmaking. We’d like to do more of that and look at these more institutional or wholesale buyers in our region. We want to identify more farmers that are growing certain products in the region, and then match them up with these institutional and wholesale buyers.

I feel like transportation is one thing that I’ve heard from a couple producers that is a really big log jam right now. I could see that being something someone’s going to need to figure out.

Prairie Five, for example, is doing a ton of transportation in our region, just moving people around. And they also are doing meal deliveries with refrigerated trucks, so they’ve got some sense of what transportation in this region looks like. So we are hoping to just be able to learn from them a little bit about their experiences and what they’ve learned about coordinated transportation.

Brian: I’ve talked to a couple of people involved with food hubs, including Beverly Dougherty, who does the Real Food Hub in Willmar, which is kind of near here. And she has a van that they’ve rented and they pick up food from farmers, aggregate it, and then deliver it to folks. Do you see food hubs playing a bigger role here? I know that they’ve been hit and miss. Some seem to get going, and then they just run out of steam. But Beverly’s food hub seems to be have a little head of steam behind it.

Scott: You’ve talked to Bev, so you kind of know she’s a firecracker. I wish we had 10 more Bev’s out here, because we’d get a lot done. I think the neat thing about what they’re doing is they have one transportation route that goes up to Morris and back. And then, as a result of some of the work we’ve done with the asset mapping and some of this work we’ve been doing through local food systems, they created a separate route that kind of goes out to Madison, through Montevideo, down to Granite Falls and back up to Willmar, where they’re based out of. And they drop off produce, but they also are buying produce from local producers as well.

I think the other big role that food hubs could really be playing is with farm-to-school. I think there’s something about what food hubs are doing in terms of aggregation and distribution and figuring those pieces out as a one-stop-shop entity that fits nicely with producers as well as school districts. And I know many school districts that are doing farm-to-school and they are finding that buying things from 20 different producers can be just crazy. And something like a food hub that is connected in with some of the other food hubs in the regions has the capacity to be able to be the one buyer for producers, so a producer doesn’t have to work with five different school districts.

And on the flip side, they also can be the one source that the school districts are buying from. There’s a role for that middleman position out here, for sure, when it comes to those orders.

Brian: I know you live just outside of town here in Granite Falls, and you have deep connections to the community, deep roots here. This must be kind of fun to see, to maybe think about planting the seeds of what a future food system could look like in this area.

Scott: Absolutely. I spend most of my days working with producers and organizing meetings with producers, which is pretty fun. They are great groups of people to be in meetings with, oftentimes with really good food when we do potlucks, especially when we’ve been doing a lot of meetings up at the Madison Mercantile. It’s awesome to see the intersections of community and our food all coming together in one spot. Just the vibrancy that brings into a community is pretty amazing.

You know, there’s definitely long days but I feel privileged to be able to do this work for sure. I live out here, so I’m hopefully going to be directly benefiting from the fruits and vegetables of my labor. It’s definitely in my self-interest to grow this kind of work. But it’s also for my kids too. My kids are going to be in the school district out here and when they’re being served meals it would be amazing to have a significant portion of that coming from producers that I’m working with, versus, you know, coming from who knows where and who knows what’s in it. That’s gotta start somewhere.

We’re talking really big pieces here, but we’re also just trying to start with just even, hey, let’s do one vegetable or one dish, and let’s just start from there. Because I think that’s really where these systems get built is through baby steps. My kid a year ago was taking baby steps, and now he’s running faster than I am. So it doesn’t take a long time either.